|

Margate Crime and Margate Punishment

Anthony Lee

8. Dover Gaol and Margate Criminals.

Before the latter part of the eighteenth century gaols were not seen as places for punishment or reform but simply as places to hold those awaiting trial, those who had to pay fines or debts, and those awaiting punishment after having been found guilty at trial. Before 1717 the punishment for all felonies was death except for the crime of petty larceny where the penalty was whipping. For minor misdemeanours the punishment could be a fine, whipping or public exposure in the stocks or pillory; after 1717 possible punishments also included transportation to the American colonies. Since Margate came under the jurisdiction of Dover, prisoners from Margate were held in the gaols of Dover. Until 1722 Dover distinguished between prisoners who were freemen of Dover and those who were not, who they referred to as ‘foreigners’; prisoners from Margate, not being freemen, counted as foreigners.1 The prison for foreigners at Dover was originally at Pennyless Bench, a paved area used by merchants for transacting their business, close to Boldware Gate, also known as Severus Gate, one of the gates in Dover’s town wall. The prison for freemen was a tower in the town wall called Standfast, also known as Butchery Gate. Debtors from the town of Dover itself were generally housed in Standfast but debtors from elsewhere in the Cinque Ports, together with those guilty of offences against the revenue laws, were imprisoned in Dover castle.2,3 Standfast became the town jail in 1722, when the system of having separate prisons for freemen and foreigners died out. Standfast continued in use until 1746 when it was condemned as unfit.

|

Figure 1. Sketch of the now demolished Butchery Gate with Steadfast Tower. [http://doverhistorian.com.] |

Standfast seems not to have been a very secure gaol, as discovered by Matthew Payne (or Pain). Payne was committed to the gaol at Dover in 1733, following his confession for robbery:4

On Monday night last one John Clun received a sum of money . . . and being in company with Matthew Payne of that place [Margate], the latter offered to accompany him home, it being 12 o’clock, which was accepted of; and being got a little out of that Town, they shook hands, and friendly parted, Clun for St Peter’s and Payne pretending to return to Margate; but the former had not gone above a mile, when he was knocked down by a person with a club, who robbed him of £6 13s 6d. Clun knowing him, on Tuesday the said Payne was taken up and examined, who at first denied the fact, but at last confessed it, signed his own confession, and was committed to Dover Castle. He was always a loose idle fellow and could never keep any Service.

Then, a month later, the Keeper of Dover gaol, Edward Green, placed an advertisement offered a reward of a guinea for his recapture:5

Whereas Matthew Pain, of St John the Baptist in the Isle of Thanet, has broke out of Gaol at Dover, early Yesterday morning, with his irons on, whoever can apprehend him, or give Notice as he may be apprehended and delivered to Edward Green, Keeper of the said Gaol, shall have a Guinea reward. Note, the said Pain is about five feet eight inches high; black hair, full visage, pretty fresh complexion, about 23 years of age, and a stout body’d man.

Following the condemning of Standfast, a house on the south side of the Market Place was purchased and fitted up as a prison. This cost Dover Corporation £260, covered by a loan raised against the security of the town storehouse and the market dues.6 The prison contained two rooms on the ground floor, and two above; one of the rooms was the Bridewell, or house of correction where vagrants were put to work. Although it was small, the gaol was only expected to house a small number of prisoners. The gaol, for example, contained just one debtor and two felons on July 25, 1775, and three debtors and four felons on February 17, 1776. Conditions in the gaol were very primitive; it must have been very cold in winter as there were no fire places. To keep down the stench, the Corporation of Dover allowed four gallons of vinegar a year to fumigate the prison, together with ‘twelve lb. of whiting, six pounds of soap, mops, brooms and pails, to keep the prison clean, and straw when the Gaoler requires it’.3

Although the prison was provided by the Corporation of Dover, and as such was a charge on the ratepayers of Dover and its members, it was run by the gaoler as a commercial business for his own profit. He was not paid a salary, but prisoners had to pay for food, heating, lighting and bedding, and the gaoler profited by acting as middleman between his charges and local tradesmen.6 The gaoler was even allowed to run a prison taproom for the sale of beer, liquors and tobacco, although this was made illegal by an Act of Parliament in 1784.8 The gaoler or his guards, the turnkeys, had no interest in trying to control aspects of the prisoners’ lives from which they received no profit and there was little or no attempt to organize the day to day lives of the prisoners; prisoners were generally left free to organize their own time. Little attempt was made to separate the various classes of prisoner, except for the separation of men and women, and debtors and felons and, indeed, rigorous separation would not have been possible in a small gaol such as that at Dover. In these circumstances it was inevitable that gaols came to be seen as schools of vice, mixing the experienced offender with young and first time offenders, and mixing convicted prisoners with those awaiting trial.8 This was a major issue for early prison reformers such as John Howard and James Neild. John Howard was unimpressed by his visit to Dover gaol in 1777; he thought the gaol ‘all close and offensive’.7 On a later visit in 1792, he still thought the gaol ‘close and offensive,’ but had seen some improvement: ‘at my last visits it was much cleaner, and quieter; and no company were drinking there, as the present keeper has no licence.‘ The keeper now received a salary of £10 as well as a chaldron of coals.9 James Neild, however, reported an unpleasant rumour he had heard about the gaoler on his visit in l801: ‘Isabella Mode,who had been three years under sentence of transportation, had a young child born in the prison, of which she said that Harris, the late Keeper, was the father’.10

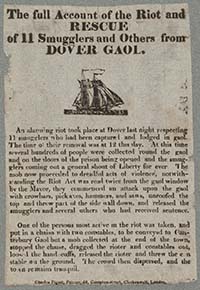

In May 1820 the gaol was destroyed by a mob angry at the arrest of a gang of smugglers.10,11 An Excise cutter had captured a smuggling galley from Folkestone with a crew of eleven who were sent to Dover gaol until those judged fit for service in the navy could be removed to one of His Majesty’s receiving ships in Chatham. On the day arranged for their removal the Mayor was informed that a large number of ‘ill-looking men’ had been seen collecting in the town. The Mayor and Magistrates, assuming the men were there to attempt the rescue of the smugglers, arranged to have a large body of constables, seamen of the preventive service, and a detachment of military drawn up to defend the prison. Two hours before the time planned for removing the smugglers, several hundred men had collected in front of the gaol and in all the approach roads, intent on rescuing them. Then:

the door of the prison was opened, and the smugglers just upon the point of being brought out, when a general shout was set up by the crowd of “Liberty for ever!" and a number of stones, brick-bats, &c. were thrown at them [the constables and soldiers]. The aspect of affairs at this time became so serious that the Mayor directed the removal of the prisoners to be suspended for the present; and it was fortunate he did, for there is little doubt that much bloodshed, and even murder, would have ensued . . . The mob, being foiled in their attempt to rescue the prisoners, proceeded to further acts of violence, and notwithstanding the Riot Act was twice read from the gaol window by the Mayor, commenced an attack on the gaol with crow-bars, pick-axes, hammers, saws &c &c, unroofed the top, and threw part of the side wall down, and, not only released the whole of the eleven smugglers, but several other prisoners confined in the gaol under sentence, and they succeeded in getting them clear off, the imposing numbers of the mob intimidating the peace officers, and others, from acting.

One of the rioters was captured and put in a chaise with two constables, to take him to Canterbury gaol, but the mob stopped the chaise, dragged the rioter and constables out, and released the rioter, despite the rioter being hand-cuffed to one of the constables. The riot was the subject of a broadside published at the time [Figure 2].

|

Figure 2. Broadside giving ‘The full account of the riot and rescue of 11 smugglers and others from Dover Gaol’, 1820. [University of Harvard]. |

The Mayor and Justices of Dover placed an advertisement in the Kentish Gazette describing how ‘a very numerous and desperate gang of smugglers, disguised in round frocks, as countrymen, and armed with bludgeons and many of them with concealed fire-arms, assembled round his Majesty’s Gaol at Dover, and having provided themselves with pickaxes, crowbars and other implements, proceeding . . . to break and enter the back part of the gaol ’. A reward of £100 was offered for information.11

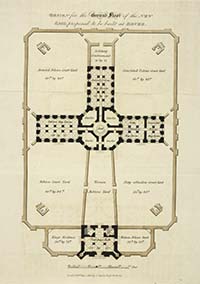

The gaol was rebuilt in 1822 to a design by the architect Richard Elsam. The first stone for the new gaol was laid in September 182212 and the gaol remained in use until 1835. Richard Elsam in 1818 in his pamphlet ‘A brief treatise on prisons’ set out his views on what made a good prison.13 He felt that it was essential to separate prisoners:

Young criminals are to be found in our national prisons daily associating, previous to their trials, with the most depraved, and abandoned characters! If these young, and it may be added unfortunate culprits, who, perhaps, have been committed for small offences, were not, previous to their committals, deeply stained with guilt; can it be expected that they will, in the event of acquittal, or punishment, be returned better members of society? Certainly not.

An additional problem according to Elsam was that prisons were now being used as places for punishing convicted offenders. A number of ‘strong prisons or penitentiary houses’ had been built specially for that purpose but many smaller prisons, like that at Dover, also were used to house convicted offenders and, Elsam suggested, ‘it seems to be but just, that they should be put under the same restraints and regimen, in common provincial gaols, as they would be in the penitentiary houses built for that particular purpose.’

The design proposed by Elsam to achieve these ends included a main entrance containing a lodge for the Turnkey and ‘hot and cold baths . . . to wash the lower order of criminals on their entrance; with a fumigating room, and an oven to purify their clothes.’ The main entrance led to a central hall where the gaoler would live, opening into three wings containing, on the ground floor, separate day or work rooms for debtors, accused felons, convicted felons, and petty offenders, with an additional room for those in solitary confinement. Above these were the prisoners’ cells, each prisoner having a separate cell. Most of the cells would have ‘louvered window shutters, with an aperture in the passage walls opposite to each of the windows to admit a free circulation of air.’ The accommodation for debtors, however, would be superior; the windows would be glazed and each of the rooms would have a small fireplace and cupboards. There would be four separate exercise yards, each 60 feet by 84 feet, one for each class of prisoner, with separate yards for women debtors, women felons, and for those prisoners who had turned King’s Evidence, who would obviously have to be separated from the other prisoners for their own safety. Each yard would contain ‘convenient and detached privies and urinals, with pumps for water, which should daily be pumped into the several pits, main-drains and sewers to be conveyed to the nearest running stream.’

|

Figure 5. The new prison at Dover as built, from Arthur Freeling, Picturesque Excursions containing upwards of four hundred views, Ackermann & C. London (nd, ca 1830). |

Although Elsam simply comments that his original design has ‘been revised and submitted to the magistrates of Dover’13 it is clear that what was built was much smaller and meaner than originally planned. In 1834 the Kentish Chronicle reported the Grand Jury at Dover as saying ‘that the Gaol so recently erected there, and which we believe is not wholly paid for, is unfit and too small for the purpose for which it was built, and for the proper classification of the prisoners. Large sums it will be remembered were spent in protracted litigation between the architect of the gaol, and the corporation, heavy expenses of which fell on the town and its liberties’.14 The Dover Telegraph, writing in 1835, commented that the gaol ‘was unadvisedly erected in the Market place in deference to public clamour’ and that, although designed for up to 50 prisoners it was unfit for the housing of more than 25.15 The gaol was visited by the Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline in 1827 and they described the prison as being ‘very ill-contrived’ despite the fact that the prison was relatively new at the time; its location in the middle of town, surrounded by public thoroughfares, meant that significant enlargement would not be possible.16 The general lack of facilities in the gaol for anything other than simple containment of the prisoners is made clear in the report. The gaol contained three small wards and yards, two for men, and one for women. Each ward contained a day-room on the ground floor, and two ‘sleeping-rooms or cells’ above. Each cell contained ‘four wooden bed-places, two below and two others over them: the bed-places are calculated for two persons in each, so that every sleeping room is intended to hold eight persons.’ The only lighting in the cells was provided by three small narrow, unglazed windows that could be closed with wooden shutters. The windows also provided the only ventilation to the cells and as the report on the prison pointed out: ‘However necessary air must be to prevent suffocation, when eight persons are crowded together in one of these rooms, it must be very difficult to admit the outward air on a winter's night, without injury to the prisoners.’ The day rooms were small ‘but tolerably good in other respects,’ and the window in each room was at least glazed. The yards were small and dank, surrounded by high walls, but each contained a ‘decent’ privy, ‘with a brick screen to hide it from view.’ Water was laid on for the prisoners to wash and cook with.

The design of the gaol meant that the separation of convicted prisoners from those awaiting trial was not possible: ‘prisoners of all descriptions are put together, viz. felons and misdemeanants, debtors and vagrants, whether men or boys. The only case of separation is that of a prisoner under sentence of death, when he has one of the two wards for males appropriated to himself, all the other prisoners being crowded into the remaining ward.’ The Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline also objected to the lack of any religious instruction; the gaol had no chapel and no chaplain and a member of the clergy only attended when a prisoner was condemned to death: ‘the governor generally appoints one of the prisoners to read the service to the others on Sunday, and when there is not one to be found who can read, he does it himself’.16

There was little opportunity for work in the gaol, although a few of the male prisoners were occupied in pumping water into a reservoir located in the central courtyard of the gaol, and others were engaged in ‘knitting night-caps, and making nets.’ Prisoners who tried to escape were put into irons: ‘one of the men confined at this time had worn irons for three months, and there seemed but little probability of their being taken off during the remainder of the term of his confinement, viz. a year and a half: he had once effected his escape from the gaol, and another attempt was apprehended, in case he had the free use of his limbs’.17

Conditions in the gaol were unhealthy. The keeper reported that there was ‘a good deal of illness in the prison, but very few deaths take place.’ There was no infirmary in the gaol and prisoners who were ill were occasionally put into a separate room, ‘when separation is necessary,’ and it was reported that ‘a medical man attends when required.’ The diet consisted of a pound of potatoes, a pint of oatmeal, and a pound of bread each day, and ¼ pound of meat every other day.16

The high cost of rebuilding the gaol in 1822 led to much acrimony in Dover.6 There was a suspicion that some of the Jurats did well out of the building contract; there were only two Jurats with experience of building, and both were employed on the gaol rebuilding. One was paid £249 19s 7d and the other £293 11s 1d. In the ten years from 1820 to 1830 the expenditure on the gaol was £6,169 10s 1d, with an additional £2,076 4s 6d being spent on law suits with the contractors, including £71 9s 6d spent in defending the Surveyor against an indictment for perjury brought by the contractors.6

|

Figure 6. The Maison Dieu at Dover, from Arthur Freeling, Picturesque Excursions containing upwards of four hundred views, Ackermann & C. London (nd, ca 1840). |

In 1834 a fourteenth century building in the Market Place, the Maison Dieu, became available and the Corporation decided to purchase it and convert the chapel into a courtroom, and build a number of vaulted brick cells below.1 Moving the town goal to the Maison Dieu gave the Corporation an opportunity to expand the gaol and improve the conditions for the prisoners. The report on the new gaol by the Inspectors of Prisons in 1837 detailed both the improvements that had been made, and the serious failings that remained.18 The gaol was described as a ‘substantial stone building’ with exercise yards enclosed by a boundary wall 24 feet high. The prison was divided into five wards for men, and two for women, with day-rooms 18 feet by 12 feet and exercise yards 30 feet by 11 feet 6 inches. Separated from the day rooms by ‘long airy corridors’15 were fourteen ‘sleeping-cells,’ twelve for men, and two for women, each 11 feet by 9 feet, and 9 feet high. Each sleeping-cell usually housed three men, or three or more women. There were also six ‘dark cells,’ 10 feet by 6 feet, which were used both for punishment and as single sleeping cells, and two more dark cells detached from the rest of the prison, intended to be used for ‘peculiar offenders, not fully committed.’ The prison was ventilated by air-holes from the town-hall above, and by the windows. The dark cells, however, lacked ventilation and were criticised for being ‘close.’ The prison was found to be dry and warm, attributed to the thickness of the walls. Each prisoner was provided with a bed, one pillow, two blankets and one rug. The drainage of the prison was said to be good, ‘the water excellent, and the locality healthy.’

At the time of inspection in 1837, the first of the five male wards contained eight prisoners awaiting trail.18 One, who had been three months in the gaol was accused of selling stolen goods, another of stealing herrings, and a third of stealing a jacket; a Fleming, who could not speak English, was accused of stealing a watch. The other four prisoners in this ward were two boys of 15, accused of stealing shrimps, both of whom had been in the gaol for nine weeks, and two boys, aged 15 and 16, accused of stealing lead. The second ward contained five prisoners, one accused of stealing a purse, and four boys, one aged 13 who had also been accused of involvement in the shrimp-stealing incident, two, aged 13 and 15 who had also been accused of involvement in the lead-stealing incident, and one, aged 14, who had already been in gaol for seven weeks, accused of obstructing a road. The third ward contained four convicted felons, all sentenced to twelve months imprisonment with hard labour, for stealing herrings, two shoes, some rope and some potatoes, respectively. All four were employed around the gaol, one as the wardsman in charge of the ward, two working as cooks in the kitchen, and one in sweeping. The fourth ward contained three prisoners convicted of misdemeanours such as obtaining goods on false pretences and deserting a workhouse. The two occupants of the fifth ward were described as ‘miscellaneous,’ one awaiting trial for assault and the other being a debtor committed to gaol for 80 days for an unpaid debt of £4. The two female wards contained four prisoners each, seven accused of theft of items including sheets, potatoes and a brass tap, and one sentenced to nine months imprisonment for theft.

Even by the standards of 1837, many of those in the gaol seemed to be there for minor offences. This was the view of the Inspector:18

One cannot but be struck with the very trifling nature of the offences in the above calendar. With the exception of the watch charged to have been stolen by the Fleming, the value of the whole of the articles stolen would probably not amount to £5. Here are 9 boys, all under the age of 17, suffering imprisonment for weeks and months, upon the most paltry charges. Three boys had been 9 weeks in gaol, for taking a handful of shrimps out of an open shop-window! Four others had been in custody several weeks, for being concerned in taking 7 lbs of lead out of a yard, which they sold for 1d, and they were brought here from Broadstairs, 24 miles! The sentences also of the four convicted men, to 12 months' imprisonment, and hard labour, each, are apparently very severe, with reference to the offences; but the nature of their employment as cooks and cleaners defeats that part of the sentence which intended that they should be placed at hard labour.

The keeper of the prison in 1837 was William Holland, who had served as keeper in this and the previous town gaol for eleven years; he received a salary of £95 a year, together with fees of about £13 per annum. His wife was the matron, for which she was paid £10 per annum. Henry Pay was the turnkey, and he received a salary of £50. All three lived in the prison. The inspector was critical of their ‘laxity of management.’ He disliked the system of keeping order in the male wards, in which one of the prisoners in each ward was appointed as wardsman to keep order over the others. In the first ward the wardsman used corporal punishment as a way of keeping order: ‘several of the boys complained that the wardsman had beaten them with a rope’s end, which he constantly used, besides striking them with his hands. Now, it may not be easy to keep a number of idle boys in order; but that one prisoner should be permitted to castigate another is not only improper, but also illegal.‘ He also disliked the mixing of adults and children in the gaol: eight boys under the age of 17 ‘were suffering long periods of imprisonment before trial in the midst of bad associates, for very trifling offences. It is a perfect delusion to suppose that such a system is conducive either to the prevention or repression of crime.’ The solution proposed by the inspector does not now read well: ‘if these boys had been well whipped and discharged, without any imprisonment, the interests of justice and of humanity would both have been gainers.’ The inspector was also critical of the imperfect separation of male and female prisoners:

The separation of males and females is not effectual. They can speak to each other from their day-rooms; they see each other in chapel; the females who may be under punishment, or who may sleep in the solitary cells, constantly pass the men's day-rooms; and, on a late occasion, a woman stopped and conversed with the men in an indecent manner. The sleeping-cells of the women are only separated by an open-barred gate from those of the men, and they could speak to each other from the sleeping-cells. The keeper and turnkey are in the habit of going into the women's apartments, and of locking up and unlocking them, without the presence of the matron or any female officer.

As in the earlier gaol, little attempt was made to keep the prisoners busy. The only regular employment was picking oakum, or beating hemp; ‘the convicted are assigned 3 lbs of oakum to pick per day. We found some of the untried also employed in oakum-picking; such employment, if not compulsory, appears by no means unsuitable to untried prisoners, and of course the absence of any employment always adds to the mischiefs of association. The picking 3 lbs of oakum is no very hard labour; in the summer season a healthy convict ought to pick at least 5 lbs to make the labour burthensome.’ The Inspector found that there was no gambling in the gaol but that ‘the prisoners amuse themselves by playing a game with buttons, which, like any other amusement, is inconsistent with the proper discipline of a prison.’ He also complained that silence was not enforced in the gaol, the prisoners being allowed to talk quietly in the day-rooms, and that at night ‘the prisoners occasionally sing in their cells, and crow in imitation of a cock.’

There was little illness in the prison, which the Inspector attributed to the ‘labour being light and the diet good . . . The diet, indeed, appears excessive, with reference to the kind of labour. It consists weekly of 122½ oz of bread, 16 oz of meat in soup, and 112 oz of potatoes . . . besides 14 quarts of gruel. This is not only superior to the ordinary fare of a labouring man, but considerably exceeds even the tread-wheel diet of neighbouring prisons. We are quite aware of the evil arising from insufficient diet; but here it really seems in the other extreme.’ This ‘excessive’ diet was provided at a cost of 2s 4d per prisoner per week.

The Inspector interviewed a number of prisoners in the gaol, and it is worth quoting from these interviews at some length as they give such a clear picture of the prisoners’ experience in the gaol. The first, W. L., aged thirteen, was to be tried for stealing shrimps:

My father is a porter: my mother is living: I have eleven brothers and sisters: I went to school for three months, but can read very little, and cannot write: I have been on a voyage to Blyth in a collier, and have also been to sea in a fishing-boat. As I and two others were coming down the street from the fair we went up to a fish-shop, and one of the boys put his hand into the window, which was open, and took some shrimps off the counter. Nine weeks ago I was committed for trial at the sessions, which will be in about a week. I have always been in the same ward: we are unlocked at seven; then we wash, and do nothing till half-past eight, when we have breakfast: in that interval we talk to each other, or walk about the yard: after breakfast we pick oakum till twelve, then have dinner, then pick oakum till four; then supper, and in half an hour we go to bed: we sleep three in a cell, two boys committed for stealing lead sleeping in the cell with me. I have sometimes heard the prisoners in other cells ‘jawing' one another. The wardmaster is not very strict: sometimes he reports for talking loud, or quarrelling, in the day-room: we are not punished for talking quietly: we talk quietly when at work: we talk at night in a moderate manner: when I was in the dark cell one day, it was next the ward where other prisoners were, I heard them talking; but I did not talk to them.

A second, A. T., was a boy of 15 from Broadstairs, accused of stealing lead:

My father is a sailor: I have a mother and four brothers and sisters: I can read a little, and write very little: I used to be employed in cleaning knives. We took seven pounds of lead out of a yard, and got 7d for it: four besides me were engaged in it, and we shared the 7d amongst us: four of us were committed about three weeks ago: picking oakum is easy work: we are not forced to pick any particular quantity. I have twice been punished for — my bed, but I could not help it: a man was punished on Sunday for speaking to his brother, in the next ward: that is now and then done: we are allowed to talk in a quiet way: about a week since I and another boy took some kings-mark, or worsted, out of the oakum, and put it into our pockets to mend our stockings: the other boy and I quarrelled about it, because he wanted to have it all: the wardsman, there-upon, took up a rope and struck me across the hip once, and hit the other boy twice: the wardsman has often hit me before with his hand: he often strikes the boys in the ward: he gave C. a stripe with a rope the other day: the lad said he should report it up at the Court when he had his trial: the wardsman said if he did not hold his tongue he would hit him again . . . When we have more than we can eat we give it to whom we like. We play a game with buttons: the wardsman sometimes is spiteful and will not let us; at other times he will let us play. I was once punished for singing in the cell: G., the cook, heard me, and reported me to Mr P., the turnkey: it is a common thing in the morning for prisoners to crow in their cells like a cock.

Finally, E. W., wardsman for the third ward, sentenced to 12 months imprisonment and hard labour for stealing herrings:

I was here five weeks before trial and three weeks since: I am sentenced to twelve months' imprisonment and hard labour: I am a seafaring man: my father was a blacksmith: I cannot read or write: I was drunk when I took the [herrings]. I was first put into the ward for trial with eight others, and after trial into my present ward: three others belong to my ward: one is a cook, engaged all day in the kitchen: another is cook's mate, always in the kitchen: the third is employed every day in sweeping up, and I am wardsman, and clean the day-room and yard: the other young man has his meals with me, but not the cooks.

My task is three or four pounds of oakum to pick a-day: no one weighs or knows exactly how much I pick: I judge of the quantity for myself. In the ward before trial there is sometimes quarrelling and bad language: we were allowed to talk without noise, and so in the present ward. E. was wardsman of the former ward: E. used to tell the master if they did not mind, and master would put them in the dark cell: sometimes I would give the lads a cut with a rope: now and then he would give them a slap with his hands . . . I sleep in a cell with the cook and sweeper. I have heard crowing like a cock in one of the sleeping-cells. The work at picking oakum is not hard: I would rather have it than the tread-mill: I would rather pick oakum than be idle, and so would most: I have heard the cook's mate speak of Canterbury gaol, which was much worse than this. I live here as well as at home: I know there are many poor people who do not live half so well as they do here.

Later reports continued to complain about the way the gaol was run, in particular the way that the prisoners mixed together in the day rooms.19 In 1840 this applied in particular to the women prisoners since there was only one day ward for women. The inspector found nine female prisoners sharing this ward, including the wife of a mechanic, ‘apparently a respectable woman, under a trivial charge,’ and another woman ‘who had been nine times previously committed.’ The ward also contained two children, nine and twelve years old: ‘we have rarely seen a more wretched instance of gaol association.’ There was a particular complaint in the 1840 report about two of the cells:

We found two prisoners confined in two cells in the lower yard, which could he hardly considered better than mere out-houses; they are small, ill-ventilated, and miserable places, without bed or bedding of any kind, and having only straw for the prisoners to lie on, and were in a disgracefully dirty condition. They had each only an open pail for necessary purposes; and as this is emptied but once in the twenty-four hours, the cells were in a most offensive condition, from the effluvium arising from the contents of the open night buckets, as well as from the narrow dimensions of the cells, and the absence of proper ventilation. In these wretched places, hardly fit for the confinement of a prisoner under punishment even for a few hours, had these prisoners been kept for three days and nights, without quitting the cells for any purpose, not even for air or exercise, and on bread and water only. The male was a prisoner for trial; the female, a vagrant; they were under the surgeon's care for the itch; but we wonder that a medical man, or any of the prison authorities, should allow such places to be used for these purposes, and for the length of time for which we found them occupied. At our request, one of the visiting justices accompanied us to the cells, and he was as much surprised as ourselves.

The Inspectors blamed the magistrates for many of these problems. Prisons were generally supervised by visiting justices, appointed from amongst the magistrates, serving for a period of a year or more. In Dover the visiting justices served for just a month so that ‘by the time . . . that a magistrate becomes acquainted with the condition of the prison, has discovered the existing evils, but before he can have applied a remedy, he goes out of office; another gentleman takes his place, and must go over the ground again; so that, in point of fact, little or nothing is, or can be done.’

The Inspectors made their displeasure apparent:19

We had a long interview with the visiting justices of this prison, and brought under their notice the very many particulars in which the Gaol Acts were infringed, and the very discreditable condition in which we found the prison, with reference to some of the most important points of prison discipline. We found them well disposed to listen to our communication, and to remedy the evils of which we complained.

At the next inspection things had much improved.20 The previous keeper, William Holland, who had held the office for fifteen years, had died and his widow, who had been matron, had resigned. They had been replaced by William Coulthard, the former turnkey and his wife. The inspectors reported that ‘the new governor is an active officer, who appears to second the efforts of the visiting justices to improve the discipline of the prison.’ Although the prisoners still associated together during the day and three or more shared a sleeping cell at night, the effects of this association had been reduced by the formation of additional wards, and ‘the whole construction, discipline, and management of the prison has been materially improved, for which great credit is due to the visiting justices.’

Prisoners, particularly the younger prisoners, were punished for minor offences within the prison in a number of ways.20 G. L., a 21 year old prisoner, received three days solitary on bread and water for whistling, singing and swearing, whereas W.T. N., a 25-year old prisoner, just had his breakfast gruel stopped for talking in his night cell. J. H., aged 18, received six hours’ solitary for gambling, the punishment being cut short because he was, in the unemotive language of the report, ‘found suspended by the neck, but not dead’; for this further misbehaviour he was handcuffed for eight hours. J. H. H., just 13 years old, had his gruel stopped for supper for neglecting his work, and two weeks later was sentenced to six days’ solitary on bread and water for striking a fellow prisoner, but this was then reduced to two days. F. S., aged 16, received one days’ solitary on bread and water for bad conduct at chapel, but then received a further one days’ solitary for ‘breaking his pot in solitary.’ J. C., aged 10, whose conduct was described as ‘very bad’ received three day’s solitary on bread and water for indecent language, and two weeks later a further day’s solitary for neglecting his work, and two weeks after that six hours’ solitary for neglecting his lessons.

On the inspection visit in 1845 the inspectors were still complaining about the mixing of the prisoners:21

Prisoners here have the fullest opportunity of corrupting each other; they are necessarily associated in companies of considerable numbers; they may hold what conversation they please with each other, provided they do not create an undue disturbance; and it is manifest that they may communicate from ward to ward through the apertures in the wall which separates the wards from the corridor; they are either in idleness, or supplied only with a trifling quantity of oakum to pick; and, with the exception of mat-making, there is no provision made for teaching them trades, or any work which would develop the resources of their minds, and turn them from a corrupted to a virtuous course. No steps have been taken to afford instruction in reading or writing, or any other useful branch of education; and the assistance that is supplied, as to their spiritual concerns is, to say the most of it, of very moderate extent.

The prisoners had relatively little to fill their time:21

The prison bell is rung at a quarter before 6 in the morning, and the cells are unlocked at 6; all the prisoners then wash themselves, and, when washed, they commence their work. Breakfast is served at 8 o'clock, and half an hour is allowed for that meal. All the wards are swept out and beds laid to air, and all the dust, &c, removed to the tub for that purpose. On Wednesdays and Fridays the prisoners go to chapel at 10 o'clock in the morning. Dinners are served at noon, and one hour is allowed for dinner. The prisoners commence work at 1, and leave off at half-past 5 P.M., when suppers are served. After supper all the day wards are swept, and the dust, &c., removed to the tub. The prisoners are allowed to take exercise in the yards until they go to bed.

The inspectors proposed that the gaol should be converted into one in which the prisoners were confined in single cells, the so-called Separate System which had by then become popular, with politicians at least. They discussed this with the Mayor of Dover: ‘that gentleman is quite aware of the inefficacy of the existing system of association, and expressed an unreserved opinion in favour of separate confinement. It transpired, however, that the want of funds is likely to prevent the Corporation from entering upon this desirable alteration at the present period’.21

The gaol was next visited in 1850 and things had changed rather little.22 The Inspector concluded that ‘the moral and religious instruction of the prisoners is but imperfectly attended to.’ The chaplain lived at a ‘very considerable’ distance from the gaol and held services in the gaol at only irregular intervals. The majority of the prisoners could, at best, read and write imperfectly, and the appointment of a schoolteacher was recommended. There was still little for the prisoners to do, beyond the picking of oakum, and the Inspector recommended that a tread-wheel or crank-wheel should be provided for hard labour in the gaol.

The lack of provision for hard labour was a long standing problem in the gaol. In 1842 the Justices had written to the Town Council recommending ‘the immediate erection of a tread-mill’ because of the large numbers committed to the gaol ‘for whom adequate hard labour could not be provided.’23 Clearly nothing was done since the Town Council was still discussing the cost of a tread-wheel in 1849;24 the cost was reported to be £128 for a ‘wheel with iron work’ for twelve prisoners with an additional £200 for a building to house it.25,26 The gaoler at Dover in fact did not think that a tread-wheel was necessary; he reported that ‘the prisoners had a greater dislike to the punishment of picking oakum than the tread-wheel’.26 However, letters from Maidstone and Canterbury said that the prisoners there strongly disliked the tread-wheel and suggested that one advantage of having one was that the fear of tread-wheels was so great that vagrants would avoid entering towns that they know had them.27 This argument won the day and it was decided that a tread-wheel should be bought.27 Nevertheless, nothing was actually done and the issue was discussed again by the Town Council in May 1850.28 The Mayor argued in favour of a ‘hand machine, which had a dial plate showing the number of revolutions . . . and might be worked more or less laboriously by means of a crank attached to the machine.’ The great advantage of the hand machines were their cost, just £5 10s each. It was agreed to defer any decision about a tread-wheel and to try the hand machine for three months. The trial must have been a success since in February 1851 Dover placed an order ‘for six more hand machines’.29

The Government Inspector in 1859 reported some minor improvements.30 The inspector found that ‘there are two good baths, one for either sex, in which the prisoners are bathed on admission and once a month, afterwards. The bedding was sufficient as to warmth, but sheets are not used.’ The inspector commented on the new hand machines: ‘The hard labour performed in the gaol is that of the crank machine, besides which there is much oakum picked. The hard-labour prisoners pick 3 lbs a day; those not sentenced to hard labour pick 2 lbs. They also make mats and matting.’ There was a complaint, however, about the performance of the chaplain to the gaol: ‘it is no part of the duty required of him to converse apart with the prisoners; this duty is provided for by the rules, but it has never been required of the chaplains. The gentleman who held the office at the time of my visit, being the incumbent of a very populous parish, would be unable to perform the duty, as required by the rules, without retaining the services of another curate in his parish, for which the salary given by the magistrates would not suffice.’

Meanwhile, as described in A Charter for Margate, Margate had been trying to obtain its own charter, removing it from the jurisdiction of Dover. The Cinque Ports Act of 1855 moved some way in this direction and ended the jurisdiction of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports over civil suits, such cases now being heard at Maidstone. 31 Dover no longer objected to Margate obtaining its own charter as long as Margate continued to pay a rate to Dover to cover the debts incurred by Dover on behalf of the non-corporate members, principally those incurred in building the new gaol in Dover. This was ensured by a modification to the 1855 Cinque Ports Acts stating that the jurisdiction of the Quarter Sessions at Dover over Margate would not end until Margate was awarded its own Court of Quarter Sessions.32 Margate received its Charter of Incorporation in 1857 but was not awarded its own Quarter Sessions until 1870 so that although Margate, as a borough, appointed its own Justices with jurisdiction in Margate, all prisoners committed by the Margate Justices had to be sent to Dover to be tried at the Quarter Sessions at Dover and Margate continued to pay a Liberty Rate to Dover to cover the costs of Dover gaol. The problem was finally solved by yet another amendment of the Cinque Ports Act, passed in 1869.33 The bill stipulated that when a court of quarter sessions was granted to the borough of Margate, the Treasury would determine a capital amount that should be paid by Margate to Dover to end all financial liabilities to Dover. Margate finally got its Quarter Sessions in 1870 and stopped sending its prisoners for trial and imprisonment at Dover.

Although there were county gaols at both Maidstone and Canterbury, Maidstone had become the usual Assize town for the county and the gaol at Maidstone the principal gaol.34 Margate did, however, make some use of Canterbury gaol to house prisoners while on trial in Margate, prisoners being taken to and from Margate by train. In 1870, a man named Nicholson had been remanded to Canterbury Gaol for stealing some silver plate from Royal Crescent.35 The Superintendent of the Margate Police, T. M. Compton, together with Sergeant Jarman and Constable Kenny took the train to Canterbury to collect Nicholson and three other prisoners and return them to Margate to appear in Court. The prisoners were all handcuffed together and taken on foot from the gaol on St. Martin's Hill, down the hill, through Longport and into Burgate, heading for Canterbury West Railway Station. It was a very cold and wet night, and Compton took the prisoners into the Sun public house on Sun street at the bottom of Burgate where he, Jarman and Kenny and the prisoners had a drink before continuing on their way to the railway station. They then had to wait at the station for an hour for their train to Margate, which had been delayed, but on getting onto the train they found that Nicholson had escaped. Compton decided to leave Jarman and Kenny to search for Nicholson in Canterbury while he took the remaining three prisoners on the train to Margate, locked into the Guard’s Van. The Margate Watch Committee, in charge of the Police Force, investigated the incident but concluded ‘that this Committee have no evidence before them by which they can fix the escape of Nicholson to any act or neglect on the part of any of the Policeman in whose charge he was,’ suggesting that the small size of Nicholson's hands might have allowed him to free both from his handcuffs unobserved. They resolved ‘that prisoners in future be not allowed to enter any public house while in custody'.35

* * * *

Finally, it is necessary to say something about debtors, who were dealt with differently from other prisoners. Debtors were expected to maintain themselves in prison, buying their own food and drink, clothing and bedding; they were allowed to work in prison, as long as this did not interfere with prison regulations. Although debtors from the town of Dover were generally housed in the town jail, debtors from elsewhere in the Cinque Ports, together with those guilty of offences against the revenue laws, were imprisoned in Dover castle.2,3 In 1738, Captain Philemon Phillips, Commander of the Customs sloop at Deal, complained to the Customs Commissioners in London that when he applied to Dover for writs for the arrest of a number of smugglers he was told that there was no point as there was nowhere to keep prisoners safely in the castle. Robert Wellard, the Register of Dover Castle, reported that ‘all the prison rooms in the said Castle do now lay open, there having very lately several of the walls of the said rooms fallen in’ and that there was not a single ‘close room to put a man in sufficient to detain him for half an hour’.36 Some time later Fulbert de Dover’s tower in the castle was converted into the prison for Cinque Port debtors and offenders against the Revenue laws.2

The original debtors prison was tiny, containing just two rooms.2 The room on the ground floor was about twelve feet by thirteen feet; it usually contained just one bed, but when the prison was full, an additional bed was put in the room, standing with its feet ‘near the privy.’ On the floor above was another room, about seventeen feet in length, containing two beds, ‘with a privy, near the fire place.’ The editors of the Universal British Directory in 1791 were moved to include a plea for improvement in their entry on Dover:39

The bodar [keeper of the prison] of Dover castle . . . is also sergeant at arms. By this post he has power from the lord warden to take into his particular jurisdiction crown and other debtors under an arrest, and to shut them up, and keep them in safe custody, in a prison belonging to Fulbert de Dover’s tower – in this, as in many other jails in peculiar districts, there are several alterations necessary, and some things which ought to be rectified without the authority of parliament. It is to be hoped, that, when the state of this prison is known, some person who has the power will have the inclination to endeavour to soften the hardships which many suffer in it. There are but two rooms in this building for the confinement of the gentlemen, the creditable but unfortunate artificer, and the most abandoned of the human race; in these rooms are they obliged to eat and sleep, and (if reports speak truth) it has happened that the different sexes have been locked into the same apartment. The prisoners have not the least outlet, where they can go to breathe the fresh air, or for any other necessary purpose. To add to the horrors of this jail, there is not the least allowance of provisions either for common or crown debtors; and, if the persons who are so unfortunate as to be locked up here are not of a trade at which they can work in their confinement, they must not eat, unless their friends can afford to keep them, or the few who occasionally visit such scenes of distress cast in their mite to lighten but prolong their wretchedness.

In 1796, the Board of Ordnance spent £600 on extending the prison, adding three rooms and a yard, connected to the old tower. The yard was just twenty five feet by fifty, and was surrounded by walls 28 feet high so that the sun could not penetrate and the yard was cold and damp. The prison reformer James Neild reported that ‘putrid vegetables, dirt and ashes’ were thrown into the yard forming ‘an offensive dunghill’.37

A major problem was that someone found guilty by the Court of Exchequer would normally be sentenced to a large fine which, if he was unable to pay, resulted in his being sent to gaol, often for several years. During the time he spent in gaol, his debt would simply increase, and the only way out of the prison was ‘if a man of wealth and influence took pity on him and obtained his release’.2 John Lyon, in his history of Dover, reported ‘instances of great severity, for trifling offences against the revenue, and revenue officers . . . where families have been for years kept by the parish, while the husband has been confined in prison, until he could make his escape, and quit his country; or be discharged as a great act of clemency’.2 Lyon concluded that, although some punishment was required, it was ‘much to be lamented, that the law provides no other punishment for these offences, but that of imposing fines, such as many of them are utterly unable to pay; or, in default of such payment to drag on a life of confinement and misery for many years.’

As well as their living expenses, prisoners were charged a variety of fees.37 The first was a charge of one guinea to cover the cost of the court writ that had been issued ordering their arrest. They were then charged a group of fees amounting in all to £2 7s 4d: for arrest, £1 1s; for commitment, 13s 4d; for guard-money and a bed for the night, 4d; for discharge 6s 8d; to the yeoman porter, 2s 6d; and to the clerk of Dover castle, 3s 6d. A prisoner from Margate was also charged £1 11s 6d for the cost of the journey to Dover, so that on his first day he had already run up a debt of £4 19s 10d. A prisoner on his first day also had to pay a ‘garnish’ of 1s 6d for liquor for his fellow inmates, a custom common in many debtors’ prisons.

The cost of food and drink was high.37 A boy was sent to the town every day to fetch what was wanted, but this cost an extra 20 % on the price; ‘even a pail-full of water costs a penny.’ The prisoners had to pay a woman to clean the rooms, ‘as neither mops, pails, brooms, fire, or candle’ were provided. Neild estimated that only about one in ten could afford to pay the costs arising from their stay in the prison, which could be long: ‘a prisoner may be from ten to twenty months in this privileged Castle, at the suit of the Crown . . . without a trial or hearing before a Court of Justice.’ Neild was so shocked by conditions in the gaol that he raised funds to pave the prison yard and to buy four iron bedsteads with a pair of blankets and a coverlet for each bed, together with two stoves with integral ovens, in which the prisoners could bake or warm food.2 He also established a trust fund of £800, invested in bank annuities, to be used to pay the prison fees and allow for the discharge of prisoners.

Conditions in the prison were improved by an Act of 1814 entitled ‘An Act for the Relief of Poor Debtors, and others, confined within the Gaol of Dover Castle’ that authorized the raising of £300 annually from the Cinque Ports to provide bedding, medical attendance, medicines, and food, for those prisoners too poor to provide for themselves.38 Prisoners also raised money by begging; in the second floor was a grating through which they could let down a purse into which visitors could put money; this provided about 14s per week during the summer months when visitors were common.2,18 Conditions were much the same when the Inspectors of Prisons first visited in 1837.18 The prison at the time contained six male and two female prisoners. The prisoners were allowed to buy beer or wine, but not spirits and all the men smoked; indeed, at the 1845 inspection, ‘the place was saturated with tobacco-smoke, and was very offensive; it was, besides, dirty, and without a trace of order or neatness. There did not appear, indeed, to be any discipline worthy of the name maintained in the gaol’.21

The Cinque Ports Act of 1855, ‘An act for the better administration of justice in the Cinque Ports’ ended the jurisdiction of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports over civil cases arising in Margate and debtors from Margate would in future be housed in Maidstone gaol rather than in Dover Castle.31

References

1. S. P. H. Stratham, The history of the town and port of Dover, Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1899.

2. John Lyon, The history of the town and port of Dover and of Dover Castle with a short account of the Cinque Ports, 1813.

3. James Neild, An account of the rise, progress, and present state of the Society for the discharge and relief of persons imprisoned for small debts throughout England and Wales . . . , John Nichols and Son, London, 3rd edition, 1808.

4. Kentish Post, April 18 1733.

5. Kentish Post, May 16 1733.

6. Paul Muskett, Dover Gaol, 1700-1878, in The journal of regional and local studies, Summer 1984 pp 42-53.

7. John Howard, The state of the prisons in England and Wales, with preliminary observations, and an account of some foreign prisons, London, 1st edition, 1777.

8. J. M. Beattie, Crime and the courts in England 1660-1800, Princeton University Press, 1986.

9. John Howard, The state of the prisons in England and Wales, with preliminary observations, and an account of some foreign prisons and hospitals. London, 4th edition, 1792.

10. Trewman's Exeter Flying Post or Plymouth and Cornish Advertiser, June 1 1820.

11. Kentish Gazette, June 2 1820.

12. Kentish Gazette, September 2 1822.

13. Richard Elsam, A brief treatise on prisons . . . illustrated with an enlarged design of the new gaol about to be erected at Dover, London, 1818.

14. Kentish Chronicle, August 5 1834.

15. Dover Telegraph, August 29 1835.

16. Seventh report of the committee of the Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline and for the Reformation of Juvenile Offenders, London, 1827

17. Parliamentary Papers. First report of the commissioners appointed to inquire into the municipal corporations in England and Wales, London, 1835.

18. Parliamentary Papers. Inspectors of Prisons of Great Britain I. Home District, Second Report, London, 1837.

19. Parliamentary Papers. Fifth report of the inspectors appointed under the provisions of the act 5 & 6 Will. IV. c. 38. to visit the different prisons of Great Britain. I. Home district, London, 1840.

20. Parliamentary Papers. Sixth report of the inspectors appointed under the provisions of the act 5 & 6 Will. IV. c. 38, to visit the different prisons of Great Britain. I. Home District, London, 1841.

21. Parliamentary Papers. Tenth report of the inspectors appointed under the provisions of the act 5 & 6 Will. IV. c. 38, to visit the different prisons of Great Britain. I. Home district,

London, 1845.

22. Parliamentary Papers. Fourteenth report of the inspectors appointed under the provisions of the act 5 & 6 Will. IV. c. 38, to visit the different prisons of Great Britain. I. Home district, London, 1850.

23. Dover Telegraph, February 12 1842.

24. Dover Telegraph, February 10 1849.

25. Dover Telegraph, May 2 1849.

26. Dover Telegraph, July 7 1849.

27. Dover Telegraph, August 11 1849.

28. Dover Telegraph, May 11 1850.

29. Dover Telegraph, May 10 1851.

30. Parliamentary Papers. Inspectors of Prisons of Great Britain I. Southern District, Twenty-fourth Report, London, 1859.

31. Cinque Ports Act, 17 & 18 Vict. c 48, 1855.

32. A bill for the amendment of the Cinque Ports Act, 20 and 21 Vict, c1, 1857

33. An act to amend the Cinque Ports Act, 32 and 33 Vict, c 53, 1869.

34. Elizabeth Melling, Crime and Punishment, Kentish Sources Vol. VI, Kent County Council, 1969.

35. Mick Twyman and Alf Beeching, A Policeman’s lot, Bygone Margate Vol. 10 Nos 1-5, 2007.

36. Calendar of Treasury books and papers, 1735-1738 preserved in the Her majesty’s Public record office, March 30 1738, Report to the Treasury from the Customs Commissioners, London, on the memorial of the Duke of Dorset, Constable of Dover Castle, Wm. A. Shaw London, 1900.

37. James Neild, State of the prisons in England, Scotland, and Wales . . . not for the debtor only, but for felons also. Together with some useful documents, London, 1812.

38. An Act for the Relief of Poor Debtors, and others, confined within the Gaol of Dover Castle, 54 Geo. III. cap. 97, 1814.

39. The Universal British Directory of Trade, Commerce, and Manufacture . . . , Champanye and Whitrow, 1791.